What is it About Having Nothing?

All the most significant wisdom traditions espouse renunciation. Why?

One of my favorite things about moving to Alabama is how much less I have than when I lived in the cultural nexus of Austin, Texas. I have found that the less I have, the more I gain.

This is not the first time I have felt this way. Sitting in the Texas State Penitentiary, I noticed an odd contentment with having less. I missed my freedom and sovereignty; this experience was no walk in the park, but there was a taste of contentedness.

While in prison, one of the first books I read was the Hindu epic, the Ramayana. This is one of the original sacred Hindu texts written between 700 and 300 BC, and it concerns Lord Rama (God incarnate). At one point, Rama’s father unjustly banishes him to the forest for 14 years.

What strikes me about the story is that Rama willingly accepts the decree and gives away all his worldly possessions. He gives all employees in his service wages for fourteen years, gives away all material goods, and accepts the life of a hermit.

Similarly, Siddhartha Gautama (aka the Buddha) was born into a royal family. He famously renounced his material wealth and wandered the countryside as an ascetic. After giving up his wealth, he relied on the charity of others to survive.

Indigenous culture, if not folklore and myth, reflects a similar perspective. In the Pacific Northwest, tribes enacted a Potlach ceremony, where status in the community was derived from the generosity of gift-giving. Their social hierarchy was mediated by those who continuously gave away the most.

Living in Alabama, I’ve recently immersed myself in the Christian tradition. Attending Catholic Mass has been a unique experience (especially when paired with psychedelics). The teachings of Christianity, and Jesus Christ in particular, are also clear.

In Matthew 19:21, Jesus says: "If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasures in heaven."

Many interpretations of Jesus’ teachings suggest that the kingdom of heaven (and hell) refers to the consciousness we inhabit in the present moment—here and now, not the afterlife. If this is true, it is a clear appeal to adopt simplicity for our inner peace and contentment.

Jesus continues: "It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God." (Mark 10:23-25).

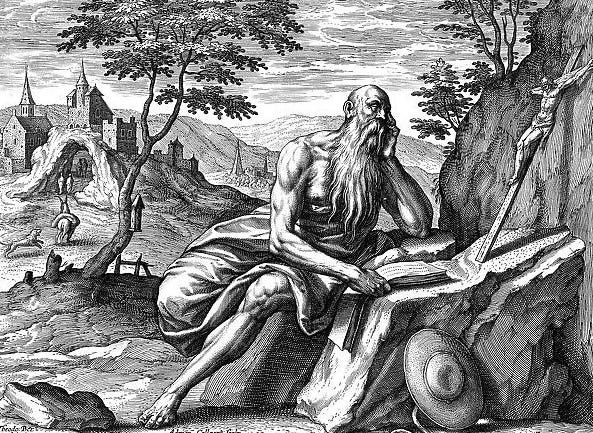

When we look at the early Christian Church, often the most lionized men were those who committed to a life of asceticism. Saint Anthony renounced his wealth and lived in a cave for 20 years as a hermit in Egypt. He is known as the Father of all Monks. Saint Colman Mac Duagh lived on spring water, nuts, and berries in Ireland while living in a cave for 7 years.

Is it possible that wealth and possessions are inimical to the highest levels of spiritual development?

I don’t know the answer. However, all wisdom traditions point to some derivation of that, and it feels uncomfortable to write and contemplate.

The American culture I live and partake in is increasingly consumptive. We valorize the wealthy and those who succeed in the capitalist system. Here, even pastors like Joel Osteen generate great wealth. Those who are left out are judged, and those who desire more equitable distribution are labeled “Communists.”

I don’t suspect the message is to give all money and possessions away. That is too simple of an interpretation. After all, Buddha did find “the middle way.” But we are reminded that we have a responsibility:

"From everyone who has been given much, much will be required; and from the one who has been entrusted with much, even more will be demanded." (Luke 12:48).

I imagine you have been entrusted with much if you are reading this. I have been given many gifts. It is up to us to decide what we choose to do with those gifts. Nobody can provide a prescription for anyone else.

I know that it feels good to live simply and ascetically. If I can give without any expectation in return (including accolades and praise), I can feed my soul by entering the consciousness of love, abundance, and humility.

One of the most poignant Biblical lines on wealth is: "For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his soul?" (Mark 8:36)

This quote resonates because it invites a more profound reflection than what giving does for others. Most people know that there is virtue in supporting others who need it. But equally important is the consciousness we gain from this pursuit. Perhaps all wisdom traditions point to the same thing, not only because it’s good for the world but also because it’s good for me.

I will not renounce all worldly possessions. I am not living in a cave. But when I feel the lure of our consumerist world, I will remember the universal simplicity, humility, and generosity embedded in all wisdom traditions. I invite you to do the same.